POEMS FOR PAINTINGS.

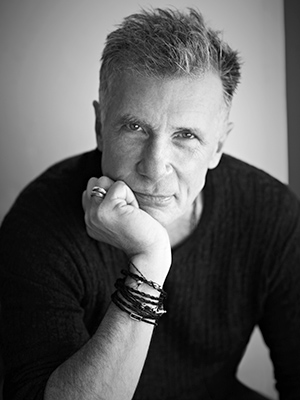

For several decades now the Irish poet Paul Durcan has been one of the heroes of the international poetry-reading scene. In the mid-eighties at one of the Newbury Street bookshops in Boston I saw him give one of the most electric and startling readings I can ever remember: he came into the polite little shop where people were drinking tea and tied them to their chairs, rifled their pockets, blasphemed their idols and had his way with their daughters. (“Are you really that intense?” the shop owner asked him, in awe. Durcan gave him an amused shrug.) I’d first discovered his work in the seventies, when the great Galway bookseller Maureen Kenny pressed Jesus, Break His Fall on me, which ends with the stark and moving piece “The Death by Heroin of Sid Vicious”. His work is prolific and highly uneven; he can fall into fantasy and garrulity, those persistent Irish failings, but in 1991, working with the National Gallery in Ireland, and in 1994, with the National Gallery in London, he produced two tours de force: Crazy About Women and Give Me Your Hand, in which he has written poems about paintings in those collections. Poems on paintings are a standard exercise for poets, but I’d say Durcan’s extended success in this form is probably unique. He uses language, not to evoke colors or textures, or to describe the paintings or place them historically, but to imagine scenarios and voices that manage to belong both to Durcan and to the paintings. There are the strange transformations and the obsession with Irish and English place names common to all of Durcan’s work; the twelve apostles become a communal gay group who take to following Christ “After living together for so many years in County Mayo / In the Delphi Valley between Leenane and Westport / In what was once a shooting lodge of Lord Sligo’s.” There are his constant bits of sly mischief and wry malice, withering with baby talk: “He is sulking because he wants his din-dins.” There are also moments of simply inspired observation: what other viewer could’ve read so sharply the expressions of the subjects of Moroni’s “Man With Two Daughters” or Rubens’ “Susanna Lunden” and spoken for them? What other poet, on the inspiration of Riminaldi’s “Cain and Abel” or Van der Werff’s “Flight into Egypt,” has so powerfully restored the brutality and heartbreak of the Biblical stories? Mischief, surrealism and all, gravity, a more than earthly serious weight, is Durcan’s natural atmosphere, whether leaping from Rousseau’s “Tiger in a Tropical Storm” to capture the flustering fear of a woman in an old age home, or honoring and restating the gravity of Cezanne’s “Old Woman with a Rosary.” Startlement and gravity: these are the words that strike me time and again, trying to describe Durcan and his work. At the London National Gallery exhibit when Give Me Your Hand was published, I observed a woman who was looking at Joshua Reynolds’ “Banastre Tarleton,” who then read Durcan’s poem—about a man remembering his rugby-champ son who has died of AIDS—and then gasped, fell backwards into a chair, and began sobbing openly. Jesus, break our fall.

Glenn Shea (Book Barn) Niantic, Connecticut