On being stubborn

from an interview in Jacket2 (April 20, 2005)at Studio 111 at the University of Pennsylvania.

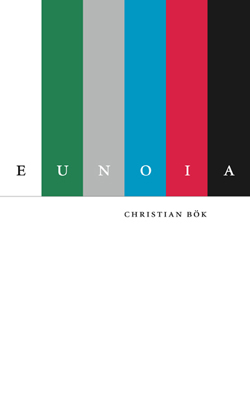

Bök: The word eunoia is spelled E-U-N-O-I-A. It’s the shortest word in English to contain all the vowels, and it means quite literally, “beautiful thinking.” It’s probably my favorite word in the language. When I first encountered this word, I thought that it would be a great title for a book.

In order to write Eunoia, I had to write five different stories: five narratives, each of which uses only one vowel. In the first chapter, only the letter A appears; in the second chapter, only the letter E appears, etc.

I did this work by first reading the Third Webster’s New International Dictionary, a three-volume dictionary. I read it five times. It has over one and a half million entries, so I had to look at about seven and a half million words in the course of accumulating the requisite vocabulary. I then sorted all the words into topical categories by hand. I didn’t use a computer to do the searching or the sorting, because I thought that it would take about as long to learn the software necessary to do such a task as it would take to actually do it by hand, and I wanted to get started. So I just simply threw myself into the task. I thought that getting the vocabulary was going to be the most arduous part of the work — sorting it into parts of speech, figuring out what the topical categories might be amongst those words, all in an effort to determine what could be said with them. Then I proceeded to arrange them, like a jigsaw puzzle, into something that would be intelligible and that would have a kind of artful, poetic value.

It turned out that the actual search for the words themselves was the easiest part of the work. The remaining seven years required to produce the book involved a tremendous amount of labor and a kind of stubborn commitment, all under very disappointing and desperate conditions.

If the book reveals anything about me personally, I think that it reveals something about my stubborn mindedness — or my obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Bök: When I was working on the book, I noticed lots of spooky moments in my activity. There’s a great deal of paranoia in Eunoia. I began to think that the vowels were, in some way, conspiring amongst themselves to speak on their own behalf. Whenever there were these kind of synchronistic coincidences, where words would fall into place and suddenly say something that seemed very uncanny, if not sublime, then I knew that the work was going well.

But such events occurred with sufficient infrequency that, most of the time, I was in a state of really black desperation. Nevertheless, these little moments of euphoria would occur. These little moments of spookiness would occur with just enough regularity that I would actually feel reinspired to continue the labor necessary to complete the work. When I was finished, I felt a kind of breathless elation at having completed such a lengthy project. Suddenly I realized that my faith in the actual language itself, its ability to work under these extremely adverse conditions, was well warranted. Language is extremely flexible and, in a certain sense, it can’t be censored. I felt a great deal of optimism about this fact when I finished the book.

Bök: The word eunoia is spelled E-U-N-O-I-A. It’s the shortest word in English to contain all the vowels, and it means quite literally, “beautiful thinking.” It’s probably my favorite word in the language. When I first encountered this word, I thought that it would be a great title for a book.

Bök: The word eunoia is spelled E-U-N-O-I-A. It’s the shortest word in English to contain all the vowels, and it means quite literally, “beautiful thinking.” It’s probably my favorite word in the language. When I first encountered this word, I thought that it would be a great title for a book.

In order to write Eunoia, I had to write five different stories: five narratives, each of which uses only one vowel. In the first chapter, only the letter A appears; in the second chapter, only the letter E appears, etc.

I did this work by first reading the Third Webster’s New International Dictionary, a three-volume dictionary. I read it five times. It has over one and a half million entries, so I had to look at about seven and a half million words in the course of accumulating the requisite vocabulary. I then sorted all the words into topical categories by hand. I didn’t use a computer to do the searching or the sorting, because I thought that it would take about as long to learn the software necessary to do such a task as it would take to actually do it by hand, and I wanted to get started. So I just simply threw myself into the task. I thought that getting the vocabulary was going to be the most arduous part of the work — sorting it into parts of speech, figuring out what the topical categories might be amongst those words, all in an effort to determine what could be said with them. Then I proceeded to arrange them, like a jigsaw puzzle, into something that would be intelligible and that would have a kind of artful, poetic value.

It turned out that the actual search for the words themselves was the easiest part of the work. The remaining seven years required to produce the book involved a tremendous amount of labor and a kind of stubborn commitment, all under very disappointing and desperate conditions.

If the book reveals anything about me personally, I think that it reveals something about my stubborn mindedness — or my obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Bök: When I was working on the book, I noticed lots of spooky moments in my activity. There’s a great deal of paranoia in Eunoia. I began to think that the vowels were, in some way, conspiring amongst themselves to speak on their own behalf. Whenever there were these kind of synchronistic coincidences, where words would fall into place and suddenly say something that seemed very uncanny, if not sublime, then I knew that the work was going well.

But such events occurred with sufficient infrequency that, most of the time, I was in a state of really black desperation. Nevertheless, these little moments of euphoria would occur. These little moments of spookiness would occur with just enough regularity that I would actually feel reinspired to continue the labor necessary to complete the work. When I was finished, I felt a kind of breathless elation at having completed such a lengthy project. Suddenly I realized that my faith in the actual language itself, its ability to work under these extremely adverse conditions, was well warranted. Language is extremely flexible and, in a certain sense, it can’t be censored. I felt a great deal of optimism about this fact when I finished the book.

Bök: I have no problem with such poetic forms. My only complaint about them is that they do not feel much incentive to innovate, to produce something new in order to reinvent themselves in a manner which is exciting and stimulating. To me, it’s not so important that poetic works actually demonstrate some sort of formalistic character, so long as they have some kind of innovative rationale for their practice. I’m not making a case for a return to a rigorous formality. I’m not that fascistic or schoolmarmish in my sensibilities. I did this project, thinking that it was a kind of experimental work. I didn’t know if it could be done, and I merely conducted the experiment to see what would happen. To me, that’s what writing poetry is about. It’s a kind of heuristic activity, where you indulge in a completely exploratory adventure through language itself.

Bök: In Eunoia, the five chapters have a thematic thread, which runs throughout the entire book. Every chapter must allude to the art of writing. All the chapters have to describe a culinary banquet, a prurient debauch, a pastoral tableaux, and a nautical voyage. These four scenarios are indicative of a vocabulary common to all the five vowels. It’s possible, for example, to say something erotic or culinary in theme throughout all the vowels, because they actually have this vocabulary in common. I wanted there to be a sort of thematic consistency across the entire book. I didn’t want it to be just five separate, individual stories that had no correlations with each other. I wanted there to be some sort of thematic parallelism — and it just so happened that these were the lexicons that were common to the five vowels. So, I included them in the story.

Coincidentally, those four scenarios are also the kinds of scenarios that you typically see in Greek epic poetry. For me, the word eunoia, which is originally from Greek, means quite literally goodwill— it was a term coined by Aristotle to describe the frame of mind that you have to be in, in order to make a friend. It reflects a kind of neoclassical set of values about beautiful thinking. Certainly, there is a kind of classical story in Eunoia. The retelling of the Iliad in chapter E, for example, alludes to these four scenarios, which are common to a classical form of storytelling. You would find these scenes in such an epic.

Bök: If you’re suggesting that I’ve demonstrated that it’s possible for a person to be an avant-garde poet and actually mean something, then right, I agree. When indulging in this kind of formalism, I could say yes — what seems true about any combination of words, according to any series of formal rationales, is that what we call meaning is really a side effect of a particular kind of activity. No matter what combination of words that I might use, no matter how they are arranged or disposed, no matter what kind of formalities are brought to bear upon them, you’re going to find some sort of way to make those associations mean something to you. It seems to me that meaning is always the side effect of such an activity.

T. S. Eliot used to say that meaning was the meat that the burglar threw to the dog. You had to put some meaning in the poem so that something else could take place. You had to satisfy those readers who were begging for some sort of rationale, some sort of purpose for this activity, which, in many respects, is done for its own sake — as a kind of hedonistic enjoyment of language, language free from the need to mean. It takes a little holiday. That’s what’s going on in Eunoia: language has taken a little holiday from the dictionary. I’ve merely shown some sort of incipient, possible combinations and permutations of the words, all of which are actually imminent within the dictionary, within the language itself, but which have been somewhat occluded or eclipsed by other activities in language. That’s what many poets are trying to do nowadays. Certainly, the Language poets do that as well. They’re attempting to show various aspects of ideology in meaningful production, aspects occluded by standard, normative uses of the language.

No comments:

Post a Comment